All in the kitchen

August 2004

Christie Smythe Photos: Deborah Silliman

Harwich friends balance success of jelly business with family

It all started when two Harwich friends, Tina Labossiere and Debbie Greiner, were looking for an at-home business to run while raising their kids. They tried making stuffed bunnies, snowmen and velvet stockings.

But they had more success selling Greiner’s pepper jelly at a craft show. At her husband’s suggestion, Greiner added cranberries – and things really started to gel.

Over four years, the two friends have garnered a following on the craft show and festival circuit selling under their Cranberry Harvest label. They also broke into the wholesale market, placing jelly in Lamberts Market in Harwich Port, Ferretti’s Market in Brewster, and Wild Oats Natural Food in Harwich Port.

Then, they got their big break. A corporate higher-up from Stop Shop had a taste of their jelly at a part they earned a spot on the supermarket’s Cape shelves.

These days, while demand continues to grow, their business is still right where it began: in Greiner’s kitchen.

The kitchen is licensed to process commercial foods, but the partners still use Greiner’s large pots, the four-burner stove, a hot plate and a food processor to make jellies in eight flavors. They use the microwave clock to time the pectin – the agent that thickens the jelly. Some nights, they’re up until 2 a.m. cooking jelly in 10- or 11-jar batches, to meet delivery deadlines.

And they do it all while looking after their combined six children, ages — to 11.

Greiner and Labossiere are certainly not the first Cape Codders to attempt an at-home specialty foods business. Many try but wind up dropping out after attempting to keep up with production and distribution demands, said Elizabeth Bridgewater, director of economic development programs for the Lower Cape Community Development Corp.

A day of jelly cooking in Greiner’s kitchen shows why. It’s a lot of hard work mixed with a little chaos.

One recent Thursday, Labossiere arrived about 9:10 a.m. with two boys and 16 bags of sugar.

By 10 a.m., the chopping and other prep work had been done, and the two were at their stations.

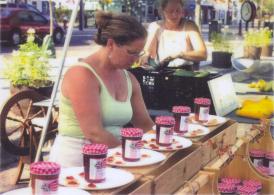

Labossiere always stands behind the island and spoons hot jelly into jars, which they sell for $5 each.

Greiner, who does virtually everything else, dances between the sink, the stove top and the counter. Lightning fast, she jumped from mixing ingredients at the counter, to the boiling mixture on the stove, back to the counter where full jars were boiling in a pot on a hot plate to finish processing the jell seal the lids.

Work trucked along until about 11 a.m., when Labossiere took her sons – Sam, 11, and Alex, 9 – to baseball practice. When she left, Greiner took a call for her husband’s charter boat business, and almost ruined a pot of jelly.

“I almost boiled over,” she said when Labossiere came back.

Quiet resumed until three of Greiner’s children – Doug, 11, Madison, 9, and Jill, 5 – were dropped off after a night at Bible camp. Greiner’s dance became more intricate, as waist-high bodies scampered around her, looking for food. After finding Lunchables in the fridge, they ate and ran off to play.

By mid-afternoon, the day had obviously taken a toll on Greiner and Labossiere. Clouds of steam rose from the pots and the dishwasher, settling in a heavy, sugar and vinegar-scented haze. In tank tops, both Greiner and Labossiere looked hot and haggard.

“We each have our own aches and pains,” Greiner said.

Repeated twisting motions have taken a toll on Labossiere’s wrists. Greiner’s back aches after hours mixing ingredients, tending to boiling pots and pouring pectin. Greiner paused for stretch breaks. She started forgetting whether she had added the pectin.

When Labossiere left to pick up her boys, Greiner ruined one pot with a double dose of pectin, and poured the contents down the bathroom toilet.

When the last batch of jelly was on the stove – by about 2:30 p.m. – Greiner walked to the living room and flopped down on the rug.

Minutes later, she sat up, smiling, and wrapped her arms around 1-year-old Marissa, who had been toddling around the living room in her diaper.

It’s hard work, said Labossiere and Greiner as they finished and cleaned up. They know of other jelly makers who simply burned out when they started distributing to restaurants and stores. But both said they still enjoy the work.

“We’re still with our kids all day,” Greiner said. “We’re with our kids more than anyone else is with their kids.”

Walk into Deb Greiner’s home kitchen on any given weekday, and she and Tina Labossiere are probably making jam. The taste and the charm in each jar is derived from the personal handling each receives. Even as their business has grown, they’ve kept it personal. Recently, someone asked Greiner for her card in a .pdf file so that he could reprint it. Greiner, who tracks all her business in an old-fashioned black and white marble notebook, responded, “PD what?” Undeterred, the person asked her to have her advertising people send it along. “My advertising people?” she responded, incredulously. “You think I have advertising people? Uh-huh. Tina and I do everything ourselves. That’s why some of the labels are askew. We’ve put them on the jars after a few glasses of wine!”

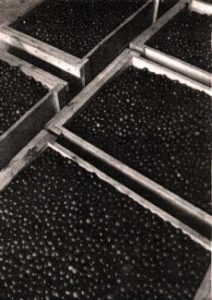

Walk into Deb Greiner’s home kitchen on any given weekday, and she and Tina Labossiere are probably making jam. The taste and the charm in each jar is derived from the personal handling each receives. Even as their business has grown, they’ve kept it personal. Recently, someone asked Greiner for her card in a .pdf file so that he could reprint it. Greiner, who tracks all her business in an old-fashioned black and white marble notebook, responded, “PD what?” Undeterred, the person asked her to have her advertising people send it along. “My advertising people?” she responded, incredulously. “You think I have advertising people? Uh-huh. Tina and I do everything ourselves. That’s why some of the labels are askew. We’ve put them on the jars after a few glasses of wine!” Yes, they’re having fun, but they’re also producing award-winning jam with cranberries grown and harvested within walking distance of Deb’s Harwich home. But if you point that out, she’s careful to be clear that she would never walk over to get the cranberries. She’ll drive, thank you. And when you take a look around her kitchen – crowded with jam jars cooling, a carton of red peppers, a dishwasher running jam jars, a pot on the stove cooking jam, kids’ drawings and schedules crowding the refrigerators and cabinets – you get the picture. Greiner and Labossiere really don’t have time for a leisurely walk over to the cranberry farm.

Yes, they’re having fun, but they’re also producing award-winning jam with cranberries grown and harvested within walking distance of Deb’s Harwich home. But if you point that out, she’s careful to be clear that she would never walk over to get the cranberries. She’ll drive, thank you. And when you take a look around her kitchen – crowded with jam jars cooling, a carton of red peppers, a dishwasher running jam jars, a pot on the stove cooking jam, kids’ drawings and schedules crowding the refrigerators and cabinets – you get the picture. Greiner and Labossiere really don’t have time for a leisurely walk over to the cranberry farm.

At the Orleans market, it’s not unusual to find a line snaking down the aisle of vendors as people wait their turn to select from just opened crates of beefy tomatoes or verdant chard still damp from the morning dew.

At the Orleans market, it’s not unusual to find a line snaking down the aisle of vendors as people wait their turn to select from just opened crates of beefy tomatoes or verdant chard still damp from the morning dew. For 10 years, Debbie Grenier and Tina Labossiere have really been cooking. Literally.

For 10 years, Debbie Grenier and Tina Labossiere have really been cooking. Literally. “The kids have always helped out since the time they could walk. But now the older ones can sometimes do a smaller show for us, like at the senior center or something, and it’s kind of nice,” says Labossiere. “And they seem to enjoy it as well. It gives them experience dealing with people, and working around money, and having to be pleasant. Debbie and I know we could not do this without the help of family and friends. We get a lot of it. The two of us are very fortunate. We have a lot of friends on the Cape, and the family contributes a lot—they come when we’re in desperate need! Debbie’s parents will come all the way from New Jersey, and you’ll see them at the Cranberry Festival. They always come and help us out, because it’s one of our biggest shows of the year. And they love coming, too. They love being here.”

“The kids have always helped out since the time they could walk. But now the older ones can sometimes do a smaller show for us, like at the senior center or something, and it’s kind of nice,” says Labossiere. “And they seem to enjoy it as well. It gives them experience dealing with people, and working around money, and having to be pleasant. Debbie and I know we could not do this without the help of family and friends. We get a lot of it. The two of us are very fortunate. We have a lot of friends on the Cape, and the family contributes a lot—they come when we’re in desperate need! Debbie’s parents will come all the way from New Jersey, and you’ll see them at the Cranberry Festival. They always come and help us out, because it’s one of our biggest shows of the year. And they love coming, too. They love being here.”